On 15 December 2013, barely two years after South Sudan celebrated independence, the promise of a new nation collapsed into violence. Political tensions between President Salva Kiir and his former Vice President Dr. Riek Machar erupted into one of the darkest chapters in the country’s short history. What started as a power struggle within the ruling SPLM quickly descended into widespread ethnic bloodshed, exposing fragile institutions and deep historical grievances.

According to United Nations reports, soldiers loyal to the president and allied militias carried out targeted killings of Nuer civilians in Juba and its surrounding neighborhoods. Homes were raided, people were pulled from hiding places, and entire families were wiped out in what later became known as the Juba Nuer massacre.

Between 15 and 18 December 2013, UN human rights investigations estimate that between 47,000 and 50,000 Nuer people were killed—most of them unarmed civilians. Thousands more fled for their lives, while bodies were dumped in mass graves or thrown into the River Nile.

The government disputed these figures, insisting that such large-scale killings did not take place in Juba. In response to growing pressure, President Kiir established a national investigative committee.

Separately, the African Union formed an independent Commission of Inquiry, led by former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo, which later recommended the creation of a Hybrid Court to try those accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

A regional political analyst later observed “December 15 was not just the start of a war; it was the collapse of trust between communities that had hoped independence would protect them.”

The massacre shattered social cohesion and ignited a full-scale civil war that would ravage South Sudan for years. Fighting spread far beyond the capital, engulfing Jonglei, Upper Nile, and Unity States.

Government forces later renamed the South Sudan People’s Defence Forces (SSPDF) clashed with the Sudan People’s Liberation Army-In Opposition (SPLA-IO) loyal to Machar, alongside allied youth militias such as the White Army.

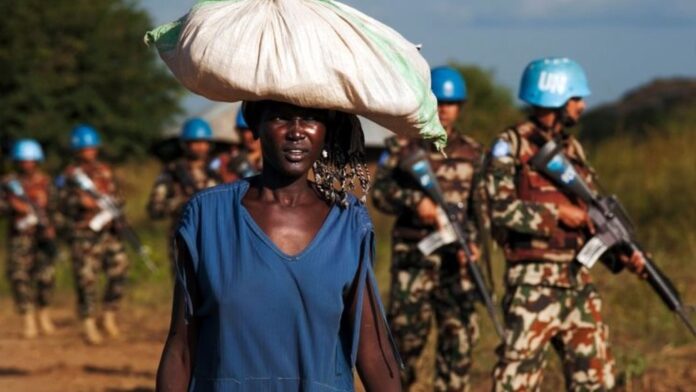

The conflict killed hundreds of thousands and displaced millions, creating one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises.

Several senior political leaders were arrested in Juba and accused of plotting a coup. They were later released without trial and relocated to Kenya, which acted as a guarantor, a move critics said highlighted the weakness of South Sudan’s justice system.

In 2015, the regional bloc IGAD brokered a peace deal known as the Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (ARCSS). The agreement returned Dr. Riek Machar to Juba as First Vice President in a transitional unity government.

He arrived with a heavily armed bodyguard an image that symbolized how fragile the peace truly was.That fragile calm collapsed in July 2016, when fighting erupted at the State House, pitting bodyguards loyal to the president against those of Machar. Machar fled the country, and the peace deal effectively fell apart.

A South Sudanese political commentator said “we signed peace, but we did not disarm our fears. The guns were louder than the signatures.”

In September 2018, the same agreement was revitalized (R-ARCSS). Once again, Kiir and Machar agreed to share power, formally ending the civil war that began in 2013. Machar returned as First Vice President, and the deal promised security sector reform, constitutional review, and national elections. Yet implementation remained slow and uneven.

In 2025, political tensions resurfaced dramatically when the government charged Dr. Riek Machar and several of his allies with treason, murder, and crimes against humanity, linked to clashes in Nasir involving the Nuer White Army. His arrest sparked widespread concern among regional and international observers.

The United Nations warned that the prosecution risked undermining the peace agreement.

“Selective justice in a fragile post-conflict state can reopen wounds rather than heal them,” one UN expert cautioned.

Beyond the political battlefield, the war devastated South Sudan’s economy. Once buoyed by oil revenues, the country’s finances collapsed under the weight of conflict and instability.

South Sudan depends almost entirely on oil exports, which flow through pipelines crossing Sudan. Repeated shutdowns caused by fighting, insecurity, and regional conflict have slashed government revenue and crippled economic planning. Civil servants went unpaid, inflation soared, and basic services collapsed.

Humanitarian needs grew as fighting disrupted farming and trade. Foreign aid, food security, and healthcare systems came under severe strain. Donor countries threatened to reduce assistance, citing insecurity and governance failures. Millions were pushed into extreme poverty, forced to flee their homes, or dependent on humanitarian aid for survival.

An economist based in Juba summed it up bluntly “the war did not just destroy lives; it destroyed the future—schools, farms, institutions, and hope.”

Every year on 15 December, South Sudanese pause to remember a painful turning point the day political rivalry and ethnic division exploded into violence and changed the nation forever. While peace agreements have sought to end the cycle of war, the legacy of distrust, broken promises, unresolved justice, and ongoing political trials continues to haunt the country.

The road to lasting stability remains long. Economic recovery, justice for victims, and genuine national reconciliation are still deeply intertwined with the wounds of the past. Until those wounds are addressed, 15 December will remain not only a date on the calendar, but a reminder of how fragile peace can be achieved.